The Brothers Grimm, Jacob (1785–1863) and Wilhelm Grimm (1786–1859), were German academics, linguists, cultural researchers, lexicographers and authors who together specialized in collecting and publishing folklore during the 19th century. They were among the best-known storytellers of folk tales, and popularized stories such as "Cinderella" ("Aschenputtel"), "The Frog Prince" ("Der Froschkönig"), "The Goose-Girl" ("Die Gänsemagd"), "Hansel and Gretel" ("Hänsel und Gretel"), "Rapunzel", "Rumpelstiltskin" ("Rumpelstilzchen"),"Sleeping Beauty" ("Dornröschen"), and "Snow White" ("Schneewittchen"). Their first collection of folk tales, Children's and Household Tales (Kinder- und Hausmärchen), was published in 1812.The popularity of the Grimms' collected folk tales has endured well.

The tales are available in more than 100 languages and have been later adapted by filmmakers including Lotte Reiniger and Walt Disney, with films such as Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and Sleeping Beauty. In the mid-20th century, the tales were used as propaganda by the Third Reich; later in the 20th century psychologists such as Bruno Bettelheim reaffirmed the value of the work, in spite of the cruelty and violence in original versions of some of the tales, which the Grimms eventually sanitized.

● Rapunzel

"Rapunzel" is a German fairy tale in the collection assembled by the Brothers Grimm, and first published in 1812 as part of Children's and Household Tales. The Grimm Brothers' story is an adaptation of the fairy tale Rapunzel by Friedrich Schulz published in 1790. The Schulz version is based on Persinette by Charlotte-Rose de Caumont de La Force originally published in 1698 which in turn was influenced by an even earlier tale, Petrosinella by Giambattista Basile, published in 1634. Its plot has been used and parodied in various media and its best known line ("Rapunzel, Rapunzel, let down your hair") is an idiom of popular culture. In volume I of the 1812 annotations (Anhang), it is listed as coming from Friedrich Schulz Kleine Romane, Book 5, pp. 269–288, published in Leipzig 1790.

Plot

A lonely couple, who wanted a child, lived next to a walled garden belonging to an evil witch named Dame Gothel. The wife, experiencing the cravings associated with the arrival of her long-awaited pregnancy, notices a rapunzel plant (or, in most translated-to-English versions[9] of the story, rampion), growing in the garden and longs for it, desperate to the point of death. One night, her husband breaks into the garden to get some for her. She makes a salad out of it and greedily eats it. It tastes so good that she longs for more. So her husband goes to get some for her a second time. As he scales the wall to return home, Dame Gothel catches him and accuses him of theft. He begs for mercy, and she agrees to be lenient, and allows him to take all he wants, on condition that the baby be given to her at birth. Desperate, he agrees. When the baby is born, Dame Gothel takes her to raise as her own and names her Rapunzel after the plant her mother craved. She grows up to be the most beautiful child in the world with long golden hair. When she reaches her twelfth year, Dame Gothel shuts her away in a tower in the middle of the woods, with neither stairs nor a door, and only one room and one window. When she visits her, she stands beneath the tower and calls out:

Rapunzel, Rapunzel, let down your hair, so that I may climb the golden stair.

Upon hearing these words, Rapunzel would wrap her long, fair hair around a hook beside the window, dropping it down to Dame Gothel, who would then climb up it to Rapunzel's tower room. (A variation on the story also has Dame Gothel imbued with the power of flight and/or levitation and Rapunzel unaware of her hair's length.)

One day, a prince rides through the forest and hears Rapunzel singing from the tower. Entranced by her ethereal voice, he searches for her and discovers the tower, but is naturally unable to enter it. He returns often, listening to her beautiful singing, and one day sees Dame Gothel visit, and thus learns how to gain access to Rapunzel. When Dame Gothel leaves, he bids Rapunzel let her hair down. When she does so, he climbs up, makes her acquaintance, and eventually asks her to marry him. She agrees.

Together they plan a means of escape, wherein he will come each night (thus avoiding the Dame Gothel who visits her by day), and bring Rapunzel a piece of silk, which she will gradually weave into a ladder. Before the plan can come to fruition, however, she foolishly gives the prince away. In the first edition of Grimm's Fairy Tales, she innocently says that her dress is getting tight around her waist (indicating pregnancy); in the second edition, she asks Dame Gothel (in a moment of forgetfulness) why it is easier for her to draw up the prince than her.[10] In anger, she cuts off Rapunzel's hair and casts her out into the wilderness to fend for herself.

When the prince calls that night, Dame Gothel lets the severed hair down to haul him up. To his horror, he finds himself staring at her instead of Rapunzel, who is nowhere to be found. When she tells him in anger that he will never see Rapunzel again, he leaps from the tower in despair and is blinded by the thorns below. In another version, she pushes him and he falls on the thorns, thus becoming blind.

For months, he wanders through the wastelands of the country and eventually comes to the wilderness where Rapunzel now lives with the twins she has given birth to, a boy and a girl. One day, as she sings, he hears her voice again, and they are reunited. When they fall into each other's arms, her tears immediately restore his sight. He leads her and their children to his kingdom, where they live happily ever after.

In some versions of the story, Rapunzel's hair magically grows back after the prince touches it.

Another version of the story ends with the revelation that Dame Gothel had untied Rapunzel's hair after the prince leapt from the tower, and it slipped from her hands and landed far below, leaving her trapped in the tower.

"The Frog Prince; or, Iron Henry" (German: Der Froschkönig oder der eiserne Heinrich, literally "The Frog King; or, The Iron Heinrich") is a fairy tale, best known through the Brothers Grimm's written version; traditionally it is the first story in their collection. The 2009 Disney film, The Princess and the Frog, is loosely based on this story.

Plot

In the tale, a spoiled princess reluctantly befriends the Frog Prince (meeting him after dropping a gold ball into a pond), who magically transforms into a handsome prince. Although in modern versions the transformation is invariably triggered by the princess kissing the frog, in the original Grimm version of the story the frog's spell was broken when the princess threw it against a wall in disgust.

In other early versions it was sufficient for the frog to spend the night on the princess' pillow.

The frog prince also has a loyal servant named Henry (or Harry) who had three iron bands affixed around his heart to prevent it from breaking in his sadness over his master's curse, but when the prince was reverted back to his human form Henry's overwhelming happiness caused all three bands to break, freeing his heart from its bonds.

A Russian folk version "Tsarevna Lyagushka" (The Frog Princess) has the male and female roles reversed: the male prince Ivan Tsarevich discovers the enchanted female frog who becomes Vasilisa the Wise, a female sorceress.

Rumpelstiltskin is the protagonist of a fairy tale that originated in Germany (where he is known as Rumpelstilzchen). The tale was collected by the Brothers Grimm in the 1812 edition of Children's and Household Tales.

Plot

In order to make himself appear superior, a miller lies to the king, telling him that his daughter can spin straw into gold (Some versions make the miller's daughter blonde and describe the "straw-into-gold" claim as a careless boast the miller makes about the way his daughter's straw-like blonde hair takes on a gold-like luster when sunshine strikes it). The king calls for the girl, shuts her in a tower room filled with straw and a spinning wheel, and demands that she spin the straw into gold by morning or he will cut off her head (other versions have the king threatening to lock her up in a dungeon forever). She has given up all hope until an imp-like creature appears in the room and spins the straw into gold for her in return for her necklace (since he only comes to people seeking a deal/trade). When the king takes the girl, on the next morning, to a larger room filled with straw to repeat the feat, the imp spins in return for the girl's ring. On the third day, when the girl has been taken to an even larger room with straw and told by the king that he will marry her if she can fill this room with gold or execute her if she cannot, the girl has nothing left with which to pay the strange creature. He extracts from her a promise that her firstborn child will be given to him, and spins the room full of gold a final time.

The king keeps his promise to marry the miller's daughter. But when their first child is born, the imp returns to claim his payment: "Now give me what you promised." The now-queen offers him all the wealth she has if she may keep the child. The imp has no interest in her riches, but finally consents to give up his claim to the child if the queen is able to guess his name within three days. Her many guesses over the first two days fail, but before the final night, she wanders out into the woods searching for the imp and comes across his remote mountain cottage and watches, unseen, as the imp hops about his fire and sings. In his song's lyrics, "tomorrow, tomorrow, tomorrow, I'll go to the king's house, nobody knows my name, I'm called 'Rumpelstiltskin'", he reveals his name. Some versions have the imp limiting the number of daily guesses to three and hence the total number of guesses allowed to a maximum of nine.

When the imp comes to the queen on the third day and she, after first feigning ignorance, reveals his true name, Rumpelstiltskin, he loses his temper and his bargain. (Versions vary about whether he accuses the devil or witches of having revealed his name to the queen.) In the 1812 edition of the Brothers Grimm tales, Rumpelstiltskin then "ran away angrily, and never came back". The ending was revised in a final 1857 edition to a more gruesome ending wherein Rumpelstiltskin "in his rage drove his right foot so far into the ground that it sank in up to his waist; then in a passion he seized the left foot with both hands and tore himself in two". Other versions have Rumpelstiltskin driving his right foot so far into the ground that he creates a chasm and falls into it, never to be seen again. In the oral version originally collected by the brothers Grimm, Rumpelstiltskin flies out of the window on a cooking ladle.

"Hansel and Gretel" (also known as Hansel and Grettel, Hansel and Grethel, or Little Brother and Little Sister) is a well-known fairy tale of German origin, recorded by the Brothers Grimm and published in 1812. Hansel and Gretel are a young brother and sister kidnapped by a cannibalistic witch living deep in the forest in a house constructed of cake and confectionery. The two children save their lives by outwitting her. The tale has been adapted to various media, most notably the opera Hänsel und Gretel (1893) by Engelbert Humperdinck and a stop-motion animated feature film made in the 1950s based on the opera. Under the Aarne–Thompson classification system, "Hansel and Gretel" is classified under Class 327.

Plot

Hansel and Gretel are young children whose father is a woodcutter. When a great famine settles over the land, the woodcutter's abusive second wife decides to take the children into the woods and abandon them there so that she and her husband will not starve to death, because the children eat too much. The woodcutter opposes the plan but finally and reluctantly submits to his wife's scheme. They are unaware that in the children's bedroom, Hansel and Gretel have overheard them. After the parents have gone to bed, Hansel sneaks out of the house and gathers as many white pebbles as he can, then returns to his room, reassuring Gretel that God will not forsake them.

The next three days, the family walks deep into the woods and Hansel lays a trail of white pebbles. After their parents leave them, the children wait for the moon to rise before following the pebbles back home. They return home safely, much to their stepmother's horror. Once again provisions become scarce and the stepmother angrily orders her husband to take the children farther into the woods and leave them there to die. Hansel and Gretel attempt to leave the house to gather more pebbles, but find the doors locked and escape impossible.

The following morning, the family treks into the woods. Hansel takes a slice of bread and leaves a trail of bread crumbs to follow home. However, after they are once again abandoned, the children find that birds have eaten the crumbs and they are lost in the woods. After days of wandering, they follow a beautiful white bird to a clearing in the woods, where they discover a large cottage built of gingerbread and cakes with window panes of clear sugar. Hungry and tired, the children begin to eat the rooftop of the candy house, when the door opens. A hideous old hag emerges and lures them inside with the promise of soft beds and delicious food. Unaware that their hostess is a bloodthirsty witch who built the gingerbread house to lure children to her to cook and eat them, the children enter the house.

The following morning the witch locks Hansel in a cage, and forces Gretel into becoming a slave. The witch force-feeds Hansel regularly to fatten him up, but he cleverly offers a bone and the witch feels it, thinking it is his finger. Due to her blindness, she is fooled into thinking Hansel is still too thin to eat. After weeks of this, the witch grows impatient and decides to eat Hansel anyway.

The witch prepares the oven for Hansel, but decides to kill Gretel as well. She coaxes Gretel to open the oven and prods her to lean over in front of it to see if the fire is hot enough. Sensing the witch's intent, Gretel pretends that she does not understand what she is being told to do. Infuriated, the witch demonstrates and Gretel instantly shoves her into the oven and slams and bolts the door shut. Gretel frees Hansel from the cage and the pair discover a vase full of treasure and precious stones. Putting the jewels into their clothing, the children set off for home.

A swan ferries them across an expanse of water and at home they find their father; his wife died from unknown causes. With the witch's wealth that they found, they all live happily ever after.

Wilhelm's character was a complete contrast to that of his brother. As a boy, he was strong and healthy, but while growing up he suffered a long and severe illness which left him weak the rest of his life. His had a less comprehensive and energetic mind than his brother, and he had less of the spirit of investigation, preferring to confine himself to some limited and definitely bounded field of work. He utilized everything that bore directly on his own studies and ignored the rest. These studies were almost always of a literary nature.

Wilhelm took great delight in music, for which his brother had but a moderate liking, and he had a remarkable gift of story-telling. Cleasby relates that “Wilhelm read a sort of farce written in the Frankfort dialect, depicting the ‘malheurs’ of a rich Frankfort tradesman on a holiday jaunt on Sunday. It was very droll, and he read it admirably.” Cleasby describes him as “an uncommonly animated, jovial fellow.” He was, accordingly, much sought in society, which he frequented much more than his brother.

A fairy tale is a type of short story that typically features European folkloric fantasy characters, such as dwarves, elves, fairies, giants, gnomes, goblins, mermaids, trolls, or witches, and usually magic or enchantments. Fairy tales may be distinguished from other folk narratives such as legends (which generally involve belief in the veracity of the events described) and explicitly moral tales, including beast fables.

In less technical contexts, the term is also used to describe something blessed with unusual happiness, as in "fairy tale ending" (a happy ending) or "fairy tale romance" (though not all fairy tales end happily). Colloquially, a "fairy tale" or "fairy story" can also mean any far-fetched story or tall tale; it is used especially of any story that not only is not true, but could not possibly be true. Legends are perceived as real; fairy tales may merge into legends, where the narrative is perceived both by teller and hearers as being grounded in historical truth. However, unlike legends and epics, they usually do not contain more than superficial references to religion and actual places, people, and events; they take place once upon a time rather than in actual times.

In traditional fairy tales or fantasy fiction, an enchantment is a magical spell that is attached, on a relatively permanent basis, to a specific person, object or location, and alters its qualities, generally in a positive way. The most widely known example is probably the spell that Cinderella's Fairy Godmother uses to turn a pumpkin into a coach. An enchantment with negative characteristics is usually instead referred to as a curse.

Conversely, enchantments are also used to describe spells that cause no real effects but deceive people, either by directly affecting their thoughts or using some kind of illusions. Enchantresses are frequently depicted as able to seduce by such magic. Other forms include deceiving people into believing that they have suffered a magical transformation.

● Legend

A legend (Latin, legenda, "things to be read") is a narrative of human actions that are perceived both by teller and listeners to take place within human history and to possess certain qualities that give the tale verisimilitude. Legend, for its active and passive participants includes no happenings that are outside the realm of "possibility" but which may include miracles. Legends may be transformed over time, in order to keep it fresh and vital, and realistic. Many legends operate within the realm of uncertainty, never being entirely believed by the participants, but also never being resolutely doubted.

● Fable

Fable is a literary genre: a succinct fictional story, in prose or verse, that features animals, mythical creatures, plants, inanimate objects, or forces of nature that are anthropomorphized (given human qualities, such as verbal communication) and that illustrates or leads to an interpretation of a moral lesson (a "moral"), which may at the end be added explicitly as a pithy maxim.

A fable differs from a parable in that the latter excludes animals, plants, inanimate objects, and forces of nature as actors that assume speech or other powers of humankind.

Usage has not always been so clearly distinguished. In the King James Version of the New Testament, "μῦθος" ("mythos") was rendered by the translators as "fable" in the First Epistle to Timothy, the Second Epistle to Timothy, the Epistle to Titus and the First Epistle of Peter.

A person who writes fables is a fabulist.

A happy ending is an ending of the plot of a work of fiction in which almost everything turns out for the best for the protagonists, their sidekicks, and almost everyone except the villains.

In storylines where the protagonists are in physical danger, a happy ending mainly consists in their surviving and successfully concluding their quest or mission. Where there is no physical danger, a happy ending is often defined as lovers consummating their love despite various factors which may have thwarted it. A considerable number of storylines combine both situations.

A happy ending is epitomized in the standard fairy tale ending phrase, "happily ever after" or "and they lived happily ever after." (One Thousand and One Nights has the more restrained formula "they lived happily until there came to them the One who Destroys all Happiness" (i.e. Death); likewise, the Russian versions of fairy tales typically end with "they lived long and happily, and died together on the same day"). Satisfactory happy endings are happy for the reader as well, in that the characters he or she sympathizes with are rewarded. However, this can also serve as an open path for a possible sequel. For example, in the 1977 film Star Wars, Luke Skywalker defeats the Galactic Empire by destroying the Death Star, however the story's happy ending has consequences that follow in The Empire Strikes Back. The concept of a permanent happy ending is specifically brought up in the Stephen King fantasy/fairy tale novel The Eyes of the Dragon which has a standard good ending for the genre, but simply states that "there were good days and bad days" afterwards.

In Shakespeare's Hamlet, Prince of Denmark, Hamlet is the protagonist. He is set in a tragic situation, where the ghost of his dead father urges him to take revenge on his uncle, who had murdered the father. Portrait of Hamlet by William Morris Hunt, oil on canvas, circa 1864.

The protagonist (from Ancient Greek πρωταγωνιστής (protagonistes), meaning "player of the first part, chief actor") or main character is a narrative's central or primary personal figure, who comes into conflict with an opposing major character or force (called the antagonist). The audience is intended to mostly identify with the protagonist. In the theatre of Ancient Greece, three actors played every main dramatic role in a tragedy; the protagonist played the leading role while the other roles were played by the deuteragonist and the tritagonist.

● Sidekick

A sidekick is a slang expression for a close companion or colleague (not necessarily in fiction) who is actually, or generally regarded as, subordinate to the one he accompanies. Some well-known fictional sidekicks are Don Quixote's Sancho Panza, Sherlock Holmes' Doctor Watson, The Lone Ranger's Tonto, The Green Hornet's Kato, Shrek's Donkey and Batman's Robin.

The term originated in pickpocket slang of the late 19th and early 20th century. The "kick" was the front side pocket of a pair of trousers, and was found to be the pocket safest from theft. Thus the pickpocket's "side-kick" became an inseparable companion.

A humorous folk etymology refers to the sidekick's accomplishments being "kicked to the side" or otherwise ignored in favor of the more charismatic lead hero.[citation needed]

One of the earliest recorded sidekicks may be Enkidu, who adopted a sidekick role to Gilgamesh after they became allies in the Epic of Gilgamesh. Other early examples are Achilles and Patroclus in the Iliad, and Moses and Aaron in the Bible.

The work was collected over many centuries by various authors, translators, and scholars across West, Central, and South Asia and North Africa. The tales themselves trace their roots back to ancient and medieval Arabic, Persian, Mesopotamian, Indian, and Egyptian folklore and literature. In particular, many tales were originally folk stories from the Caliphate era, while others, especially the frame story, are most probably drawn from the Pahlavi Persian work Hazār Afsān which in turn relied partly on Indian elements.

Synopsis

The main frame story concerns Shahryar, whom the narrator calls a "Sasanian king" ruling in "India and China".[5] He is shocked to discover that his brother's wife is unfaithful; discovering his own wife's infidelity has been even more flagrant, he has her executed: but in his bitterness and grief decides that all women are the same. Shahryar begins to marry a succession of virgins only to execute each one the next morning, before she has a chance to dishonour him. Eventually the vizier, whose duty it is to provide them, cannot find any more virgins. Scheherazade, the vizier's daughter, offers herself as the next bride and her father reluctantly agrees. On the night of their marriage, Scheherazade begins to tell the king a tale, but does not end it. The king, curious about how the story ends, is thus forced to postpone her execution in order to hear the conclusion. The next night, as soon as she finishes the tale, she begins (and only begins) a new one, and the king, eager to hear the conclusion, postpones her execution once again. So it goes on for 1,001 nights.

The tales vary widely: they include historical tales, love stories, tragedies, comedies, poems, burlesques and various forms of erotica. Numerous stories depict jinns, ghouls, apes, sorcerers, magicians, and legendary places, which are often intermingled with real people and geography, not always rationally; common protagonists include the historical Abbasid caliph Harun al-Rashid, his Grand Vizier, Jafar al-Barmaki, and the famous poet Abu Nuwas, despite the fact that these figures lived some 200 years after the fall of the Sassanid Empire in which the frame tale of Scheherazade is set. Sometimes a character in Scheherazade's tale will begin telling other characters a story of his own, and that story may have another one told within it, resulting in a richly layered narrative texture.

The different versions have different individually detailed endings (in some Scheherazade asks for a pardon, in some the king sees their children and decides not to execute his wife, in some other things happen that make the king distracted) but they all end with the king giving his wife a pardon and sparing her life.

The narrator's standards for what constitutes a cliffhanger seem broader than in modern literature. While in many cases a story is cut off with the hero in danger of losing his life or another kind of deep trouble, in some parts of the full text Scheherazade stops her narration in the middle of an exposition of abstract philosophical principles or complex points of Islamic philosophy, and in one case during a detailed description of human anatomy according to Galen—and in all these cases turns out to be justified in her belief that the king's curiosity about the sequel would buy her another day of life.

A stock character is a stereotypical person whom audiences readily recognize from frequent recurrences in a particular literary tradition. Stock characters are archetypal characters distinguished by their flatness. As a result, they tend to be easy targets for parody and to be criticized as clichés. The presence of a particular array of stock characters is a key component of many genres.

New Comedy was the first theatrical form to have access to Theophrastus’ Characters. Menander was said to be a student of Theophrastus, and has been remembered for his prototypical cooks, merchants, farmers and slave characters. Although we have few extant works of the New Comedy, the titles of Menander’s plays alone have a “Theophrastan ring": The Fisherman, The Farmer, The Superstitious Man, The Peevish Man, The Promiser, The Heiress, The Priestess, The False Accuser, The Misogynist, The Hated Man, The Shipmaster, The Slave, The Concubine, The Soldiers, The Widow, and The Noise-Shy Man.

Another early form that illustrates the beginnings of the Character is the mime. Greco-Roman mimic playlets often told the stock story of the fat, stupid husband who returned home to find his wife in bed with a lover, stock characters in themselves. Although the mimes were not confined to playing stock characters, the mimus calvus was an early reappearing character. Mimus calvus resembled Maccus, the buffoon from the Atellan Farce. The Atellan Farce is highly significant in the study of the Character because it contained the first true stock characters.[citation needed] The Atellan Farce employed four fool types. In addition to Maccus, Bucco, the glutton, Pappus, the naïve old man (the fool victim), and Dossennus, the cunning hunchback (the trickster). A fifth type, in the form of the additional character Manducus, the chattering jawed pimp, also may have appeared in the Atellan Farce, possibly out of an adaptation of Dossennus. The Roman mime, as well, was a stock fool, closely related to the Atellan fools.

Jacob Ludwig Carl Grimm (4 January 1785 – 20 September 1863) was a German philologist, jurist, and mythologist. He is known as the discoverer of Grimm's law (linguistics), the co-author with his brother Wilhelm of the monumental Deutsches Wörterbuch, the author of Deutsche Mythologie and, more popularly, as one of the Brothers Grimm and the editor of Grimm's Fairy Tales.

Jacob Grimm was born in Hanau, in Hesse-Kassel (or Hesse-Cassel). His father was a lawyer, but he died while Jacob was a child, and his mother was left with very small means. His mother's sister was lady of the chamber to the Landgravine of Hesse, and she helped to support and educate her numerous family. Jacob was sent to the public school at Kassel in 1798 with his younger brother Wilhelm (born on 24 February 1786).

In 1802, he proceeded to the University of Marburg where he studied law, a profession for which he had been destined by his father. His brother joined him at Marburg a year later, having just recovered from a long and severe illness, and likewise began the study of law.

Lexicography is divided into two separate but equally important groups:

Practical lexicography is the art or craft of compiling, writing and editing dictionaries.

Theoretical lexicography is the scholarly discipline of analyzing and describing the semantic, syntagmatic and paradigmatic relationships within the lexicon (vocabulary) of a language, developing theories of dictionary components and structures linking the data in dictionaries, the needs for information by users in specific types of situations, and how users may best access the data incorporated in printed and electronic dictionaries. This is sometimes referred to as 'metalexicography'.

A person devoted to lexicography is called a lexicographer.

General lexicography focuses on the design, compilation, use and evaluation of general dictionaries, i.e. dictionaries that provide a description of the language in general use. Such a dictionary is usually called a general dictionary or LGP dictionary (Language for General Purpose). Specialized lexicography focuses on the design, compilation, use and evaluation of specialized dictionaries, i.e. dictionaries that are devoted to a (relatively restricted) set of linguistic and factual elements of one or more specialist subject fields, e.g. legal lexicography. Such a dictionary is usually called a specialized dictionary or Language for specific purposes dictionary and following Nielsen 1994, specialized dictionaries are either multi-field, single-field or sub-field dictionaries.

There is some disagreement on the definition of lexicology, as distinct from lexicography. Some use "lexicology" as a synonym for theoretical lexicography; others use it to mean a branch of linguistics pertaining to the inventory of words in a particular language.

Academic dress is a traditional form of clothing for academic settings, primarily tertiary (and sometimes secondary) education, worn mainly by those who have been admitted to a university degree (or similar), or hold a status that entitles them to assume them (e.g., undergraduate students at certain old universities). It is also known as academicals and, in the United States, as academic regalia.

Contemporarily, it is commonly seen only at graduation ceremonies, but formerly academic dress was, and to a lesser degree in many ancient universities still is, worn daily. Today the ensembles are distinctive in some way to each institution, and generally consists of a gown (also known as a robe) with a separate hood, and usually a cap (generally either a square academic cap, a tam, or a bonnet). Academic dress is also worn by members of certain learned societies and institutions as official dress.

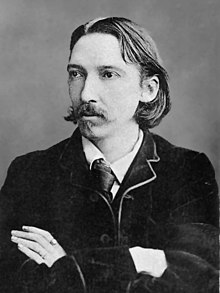

Stevenson was born at 8 Howard Place, Edinburgh, Scotland, on 13 November 1850 to Thomas Stevenson (1818–87), a leading lighthouse engineer, and his wife Margaret Isabella (née Balfour; 1829–97). He was christened Robert Lewis Balfour Stevenson. At about age 18, Stevenson was to change the spelling of "Lewis" to "Louis", and in 1873 he dropped "Balfour."

Lighthouse design was the family profession: Thomas's father (Robert's grandfather) was the famous Robert Stevenson, and both of Thomas's brothers (Robert's uncles) Alan and David, were in the same field. Indeed, even Thomas's maternal grandfather, Thomas Smith, had been in the same profession. However, Robert's mother's family were not of the same profession. Margaret's natal family, the Balfours, were gentry, tracing their lineage back to a certain Alexander Balfour who had held the lands of Inchyra in Fife in the fifteenth century. Margaret's father, Lewis Balfour (1777–1860), was a minister of the Church of Scotland at nearby Colinton. Stevenson spent the greater part of his boyhood holidays in his maternal grandfather's house. "Now I often wonder," wrote Stevenson, "what I inherited from this old minister. I must suppose, indeed, that he was fond of preaching sermons, and so am I, though I never heard it maintained that either of us loved to hear them."

Lewis Balfour and his daughter both had weak chests, so they often needed to stay in warmer climates for their health. Stevenson inherited a tendency to coughs and fevers, exacerbated when the family moved to a damp, chilly house at 1 Inverleith Terrace in 1851. The family moved again to the sunnier 17 Heriot Row when Stevenson was six years old, but the tendency to extreme sickness in winter remained with him until he was eleven. Illness would be a recurrent feature of his adult life and left him extraordinarily thin. Contemporary views were that he had tuberculosis, but more recent views are that it was bronchiectasis or even sarcoidosis.

Stevenson's parents were both devout and serious Presbyterians, but the household was not strict in its adherence to Calvinist principles. His nurse, Alison Cunningham (known as Cummy), was more fervently religious. Her Calvinism and folk beliefs were an early source of nightmares for the child, and he showed a precocious concern for religion. But she also cared for him tenderly in illness, reading to him from Bunyan and the Bible as he lay sick in bed and telling tales of the Covenanters. Stevenson recalled this time of sickness in "The Land of Counterpane" in A Child's Garden of Verses (1885), dedicating the book to his nurse.

● Treasure Island

Treasure Island is an adventure novel by Scottish author Robert Louis Stevenson, narrating a tale of "buccaneers and buried gold". It was originally serialized in the children's magazine Young Folks between 1881 and 1882 under the title Treasure Island, or the mutiny of the Hispaniola, credited to the pseudonym "Captain George North". It was first published as a book on 14 November 1883 by Cassell & Co.

Treasure Island is traditionally considered a coming-of-age story, and is noted for its atmosphere, characters, and action. It is also noted as a wry commentary on the ambiguity of morality—as seen in Long John Silver—unusual for children's literature. It is one of the most frequently dramatized of all novels. Its influence is enormous on popular perceptions of pirates, including such elements as treasure maps marked with an "X", schooners, the Black Spot, tropical islands, and one-legged seamen bearing parrots on their shoulders.

PART I—"THE OLD BUCCANEER"

An old sailor, calling himself "the captain"—real name "Billy" Bones—comes to lodge at the Admiral Benbow Inn on the west English coast during the mid-1700s, paying the innkeeper's son, Jim Hawkins, a few pennies to keep a lookout for a one-legged "seafaring man." A seaman with intact legs shows up, frightening Billy—who drinks far too much rum—into a stroke, and Billy tells Jim that his former shipmates covet the contents of his sea chest. After a visit from yet another man, Billy has another stroke and dies; Jim and his mother (his father has also died just a few days before) unlock the sea chest, finding some money, a journal, and a map. The local physician, Dr. Livesey, deduces that the map is of an island where a deceased pirate—Captain Flint—buried a vast treasure. The district squire, Trelawney, proposes buying a ship and going after the treasure, taking Livesey as ship's doctor and Jim as cabin boy.

PART II—"THE SEA COOK"

Several weeks later, Trelawney sends for Jim and Livesey and introduces them to "Long John" Silver, a one-legged Bristol tavern-keeper whom he has hired as ship's cook. (Silver enhances his outre attributes—crutch, pirate argot, etc.—with a talking parrot.) They also meet Captain Smollett, who tells them that he dislikes most of the crew on the voyage, which it seems everyone in Bristol knows is a search for treasure. After taking a few precautions, however, they set sail on Trelawny's schooner for the distant island. During the voyage the first mate, a drunkard, disappears overboard. And just before the island is sighted, Jim—concealed in an apple barrel—overhears Silver talking with two other crewmen. They are all former "gentlemen o'fortune" (pirates) in Flint's crew and have planned a mutiny. Jim alerts the captain, doctor, and squire, and they calculate that they will be seven to 19 against the mutineers and must pretend not to suspect anything until the treasure is found, when they can surprise their adversaries.

PART III—"MY SHORE ADVENTURE"

But after the ship is anchored, Silver and some of the others go ashore, and two men who refuse to join the mutiny are killed—one with so loud a scream that everyone realizes there can be no more pretense. Jim has impulsively joined the shore party and covertly witnessed Silver committing one of the murders; now, in fleeing, he encounters a half-crazed Englishman, Ben Gunn, who tells him he was marooned here and can help against the mutineers in return for passage home and part of the treasure.

PART IV—"THE STOCKADE"

Meanwhile Smollett, Trelawney, and Livesey, along with Trelawney's three servants and one of the other hands, Abraham Gray, abandon the ship and come ashore to occupy a stockade. The men still on the ship, led by the coxswain Israel Hands, run up the pirate flag. One of Trelawney's servants and one of the pirates are killed in the fight to reach the stockade, and the ship's gun keeps up a barrage upon them, to no effect, until dark, when Jim finds the stockade and joins them. The next morning Silver appears under a flag of truce, offering terms that the captain refuses, and revealing that another pirate has been killed in the night (by Gunn, Jim realizes, although Silver does not). At Smollett's refusal to surrender the map, Silver threatens an attack, and, within a short while, the attack on the stockade is launched.

PART V—"MY SEA ADVENTURE"

After a battle, the surviving mutineers retreat, having lost six men, but two more of the captain's group have been killed and Smollett himself is badly wounded. When Livesey leaves in search of Gunn, Jim runs away without permission and finds Gunn's homemade coracle. After dark, he goes out and cuts the ship adrift. The two pirates on board, Hands and O'Brien, interrupt their drunken quarrel to run on deck, but the ship—with Jim's boat in her wake—is swept out to sea on the ebb tide. Exhausted, Jim falls asleep in the boat and wakens the next morning, bobbing along on the west coast of the island, carried by a northerly current. Eventually, he encounters the ship, which seems deserted, but getting on board, he finds O'Brien dead and Hands badly wounded. He and Hands agree that they will beach the ship at an inlet on the northern coast of the island. As the ship is finally beached, Hands attempts to kill Jim, but is himself killed in the attempt. Then, after securing the ship as well as he can, Jim goes back ashore and heads for the stockade. Once there, in utter darkness, he enters the blockhouse—to be greeted by Silver and the remaining five mutineers, who have somehow taken over the stockade in his absence.

PART VI—"CAPTAIN SILVER"

Silver and the others argue about whether to kill Jim, and Silver talks them down. He tells Jim that, when everyone found the ship was gone, the captain's party agreed to a treaty whereby they gave up the stockade and the map. In the morning the doctor arrives to treat the wounded and sick pirates, and tells Silver to look out for trouble when they find the site of the treasure. After he leaves, Silver and the others set out with the map, taking Jim along as hostage. They encounter a skeleton, arms apparently oriented toward the treasure, which seriously unnerves the party. Eventually they find the treasure cache—empty. Two of the pirates charge at Silver and Jim, but are shot down by Livesey, Gray, and Gunn, from ambush. The other three run away, and Livesey explains that Gunn has long ago found the treasure and taken it to his cave.

In the next few days they load the treasure onto the ship, abandon the three remaining mutineers (with supplies and ammunition) and sail away. At their first port, where they will sign on more crew, Silver steals a bag of money and escapes. The rest sail back to Bristol and divide up the treasure. Jim says there is more left on the island, but he for one will not undertake another voyage to recover it.

● Disney - Sleeping Beauty - Once Upon A Dream

"Once Upon a Dream" is a song written in 1959 for the animated musical fantasy film Sleeping Beauty produced by Walt Disney. It is based on Tchaikovsky's ballet of the same name, more specifically the piece "Grande valse villageoise" ("The Garland Waltz"). It is the theme of Princess Aurora and Prince Philip and was performed by a chorus as an overture and third-reprise finale. Mary Costa and Bill Shirley, who were cast in the roles of Princess Aurora and Prince Philip, performed the song as a duet.

"Hansel and Gretel" is a well-known fairy tale of German origin, recorded by the Brothers Grimm and published in 1812. Hansel and Gretel are a young brother and sister kidnapped by a cannibalistic witch living deep in the forest in a house constructed of cake and confectionery. The two children save their lives by outwitting her. The tale has been adapted to various media, most notably the opera Hänsel und Gretel (1893) by Engelbert Humperdinck and a stop-motion animated feature film made in the 1950s based on the opera. Under the Aarne–Thompson classification system, "Hansel and Gretel" is classified under Class 327.

Plot

Hansel and Gretel are young children whose father is a woodcutter. When a great famine settles over the land, the woodcutter's abusive second wife decides to take the children into the woods and abandon them there so that she and her husband will not starve to death, because the children eat too much. The woodcutter opposes the plan but finally and reluctantly submits to his wife's scheme. They are unaware that in the children's bedroom, Hansel and Gretel have overheard them. After the parents have gone to bed, Hansel sneaks out of the house and gathers as many white pebbles as he can, then returns to his room, reassuring Gretel that God will not forsake them.

The next three days, the family walks deep into the woods and Hansel lays a trail of white pebbles. After their parents leave them, the children wait for the moon to rise before following the pebbles back home. They return home safely, much to their stepmother's horror. Once again provisions become scarce and the stepmother angrily orders her husband to take the children farther into the woods and leave them there to die. Hansel and Gretel attempt to leave the house to gather more pebbles, but find the doors locked and escape impossible.

The following morning, the family treks into the woods. Hansel takes a slice of bread and leaves a trail of bread crumbs to follow home. However, after they are once again abandoned, the children find that birds have eaten the crumbs and they are lost in the woods. After days of wandering, they follow a beautiful white bird to a clearing in the woods, where they discover a large cottage built of gingerbread and cakes with window panes of clear sugar. Hungry and tired, the children begin to eat the rooftop of the candy house, when the door opens. A hideous old hag emerges and lures them inside with the promise of soft beds and delicious food. Unaware that their hostess is a bloodthirsty witch who built the gingerbread house to lure children to her to cook and eat them, the children enter the house.

The following morning the witch locks Hansel in a cage, and forces Gretel into becoming a slave. The witch force-feeds Hansel regularly to fatten him up, but he cleverly offers a bone and the witch feels it, thinking it is his finger. Due to her blindness, she is fooled into thinking Hansel is still too thin to eat. After weeks of this, the witch grows impatient and decides to eat Hansel anyway.

The witch prepares the oven for Hansel, but decides to kill Gretel as well. She coaxes Gretel to open the oven and prods her to lean over in front of it to see if the fire is hot enough. Sensing the witch's intent, Gretel pretends that she does not understand what she is being told to do. Infuriated, the witch demonstrates and Gretel instantly shoves her into the oven and slams and bolts the door shut. Gretel frees Hansel from the cage and the pair discover a vase full of treasure and precious stones. Putting the jewels into their clothing, the children set off for home.

A swan ferries them across an expanse of water and at home they find their father; his wife died from unknown causes. With the witch's wealth that they found, they all live happily ever after.

Charles John Huffam Dickens was an English writer and social critic. He created some of the world's best-known fictional characters and is regarded as the greatest novelist of the Victorian era. His works enjoyed unprecedented popularity during his lifetime, and by the twentieth century critics and scholars had recognised him as a literary genius. His novels and short stories enjoy lasting popularity.

Born in Portsmouth, Dickens left school to work in a factory when his father was incarcerated in a debtors' prison. Despite his lack of formal education, he edited a weekly journal for 20 years, wrote 15 novels, five novellas, hundreds of short stories and non-fiction articles, lectured and performed extensively, was an indefatigable letter writer, and campaigned vigorously for children's rights, education, and other social reforms.

Dickens's literary success began with the 1836 serial publication of The Pickwick Papers. Within a few years he had become an international literary celebrity, famous for his humour, satire, and keen observation of character and society. His novels, most published in monthly or weekly instalments, pioneered the serial publication of narrative fiction, which became the dominant Victorian mode for novel publication.

A Christmas Carol in Prose, Being a Ghost-Story of Christmas, commonly known as A Christmas Carol, is a novella by Charles Dickens, first published in London by Chapman & Hall on 19 December 1843. The novella met with instant success and critical acclaim. A Christmas Carol tells the story of a bitter old miser named Ebenezer Scrooge and his transformation into a gentler, kindlier man after visitations by the ghost of his former business partner Jacob Marley and the Ghosts of Christmas Past, Present and Yet to Come.

The book was written at a time when the British were examining and exploring Christmas traditions from the past as well as new customs such as Christmas cards and Christmas trees. Carol singing took a new lease on life during this time. Dickens's sources for the tale appear to be many and varied, but are, principally, the humiliating experiences of his childhood, his sympathy for the poor, and various Christmas stories and fairy tales.

A Christmas Carol remains popular—having never been out of print—and has been adapted many times to film, stage, opera, and other media.

"The Gift of the Magi" is a short story, written by O. Henry (a pen name for William Sydney Porter), about a young married couple and how they deal with the challenge of buying secret Christmas gifts for each other with very little money. As a sentimental story with a moral lesson about gift-giving, it has been a popular one for adaptation, especially for presentation at Christmas time. The plot and its "twist ending" are well-known, and the ending is generally considered an example of comic irony. It was allegedly written at Pete's Tavern on Irving Place in New York City.

The story was initially published in The New York Sunday World under the title "Gifts of the Magi" on December 10, 1905. It was first published in book form in the O. Henry Anthology The Four Million in April 1906.

Summary

Mr. James Dillingham ("Young Jim") and his wife, Della, are a couple living in a modest apartment. They have only two possessions between them in which they take pride: Della's beautiful long, flowing hair, almost to her knees, and Jim's shiny gold watch, which had belonged to his father and grandfather.

On Christmas Eve, with only $1.87 in hand, and desperate to find a gift for Jim, Della sells her hair for $20 to a nearby hairdresser named Madame Sofronie, and eventually finds a platinum pocket watch fob chain for Jim's watch for $21. Satisfied with the perfect gift for Jim, Della runs home and begins to prepare pork chops for dinner.

At 7 o'clock, Della sits at a table near the door, waiting for Jim to come home. Unusually late, Jim walks in and immediately stops short at the sight of Della, who had previously prayed that she was still pretty to Jim. Della then admits to Jim that she sold her hair to buy him his present. Jim gives Della her present – an assortment of expensive hair accessories (referred to as “The Combs”), useless now that her hair is short. Della then shows Jim the chain she bought for him, to which Jim says he sold his watch to get the money to buy her combs. Although Jim and Della are now left with gifts that neither one can use, they realize how far they are willing to go to show their love for each other, and how priceless their love really is.

The story ends with the narrator comparing the pair's mutually sacrificial gifts of love with those of the Biblical Magi:

The magi, as you know, were wise men – wonderfully wise men – who brought gifts to the new-born King of the Jews in the manger. They invented the art of giving Christmas presents. Being wise, their gifts were no doubt wise ones, possibly bearing the privilege of exchange in case of duplication. And here I have lamely related to you the uneventful chronicle of two foolish children in a flat who most unwisely sacrificed for each other the greatest treasures of their house. But in a last word to the wise of these days let it be said that of all who give gifts these two were the wisest. Of all who give and receive gifts, such as they are wisest. Everywhere they are wisest. They are the Magi.

留言列表

留言列表